A Slippery and Subtle Knave – The Bank Sneak.

Of the many forms of bank robbery, the bank sneak had the safest, easiest and most lucrative method of all.

July 31, 2012

alias: JOHNSON, MITCHELL

PICKPOCKET, SHOPLIFTER

The Strange Company staffers wishes all our fellow Americans a happy Independence Day!The dark side of the Tower of London.The dark side of small town America.A 16th century manuscript about Robin Hood.The mock mayor of Stroud Green.Once upon a time, there was an ancient Roman with really freaking big feet.Something that is not--in no shape or form, absolutely not, no way in hell--a photo

More...

Strange Company - 7/4/2025

Wouldn’t you love to have interviewed Lizzie’s physician, Dr. Nomus S. Paige from Taunton, the jail doctor, ? He found her to be of sane mind and we can now confirm that he had Lizzie moved to the Wright’s quarters while she was so ill after her arraignment with bronchitis, tonsilitis and a heavy cold. We learn that she was not returned to her cell as he did not wish a relapse so close to her trial. Dr. Paige was a Dartmouth man, class of 1861. I have yet to produce a photo of him but stay tuned! His house is still standing at 74 Winthrop St, corner of Walnut in Taunton. He was married twice, with 2 children by his second wife Elizabeth Honora “Nora” Colby and they had 2 children,Katherine and Russell who both married and had families. Many of the Paiges are buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Taunton. Dr. Paige died in April of 1919- I bet he had plenty of stories to tell about his famous patient in 1893!! He was a popular Taunton doctor at Morton Hospital and had a distinguished career. Dr. Paige refuted the story that Lizzie was losing her mind being incarcerated at the jail, a story which was appearing in national newspapers just before the trial. Mt. Pleasant Cemetery, Taunton, courtesy of Find A Grave. 74 Winthrop St., corner of Walnut, home of Dr. Paige, courtesy of Google Maps Obituary for Dr. Paige, Boston Globe April 17, 1919

More...

Lizzie Borden: Warps and Wefts - 5/24/2025

Dr. John W. Hughes was a restless, intemperate man whose life never ran smoothly. When his home life turned sour, he found love with a woman half his age. Then, he lost her through an act of deception, and in a fit of drunken rage, Dr. Hughes killed his one true love.Read the full story here: The Bedford Murder.

More...

Murder By Gaslight - 7/5/2025

How did New Yorkers get through sweltering summer days before the invention and widespread use of air conditioning? Well, a lot of it depended on your income bracket. If you were wealthy, you likely waited out the summer at a seaside resort like Newport or on a country estate cooled by mountains or river breezes. […]

More...

Ephemeral New York - 6/30/2025

Youth With Executioner by Nuremberg native Albrecht Dürer … although it’s dated to 1493, which was during a period of several years when Dürer worked abroad. November 13 [1617]. Burnt alive here a miller of Manberna, who however was lately … Continue reading

More...

Executed Today - 11/13/2020

The Strange Company staffers wishes all our fellow Americans a happy Independence Day!The dark side of the Tower of London.The dark side of small town America.A 16th century manuscript about Robin Hood.The mock mayor of Stroud Green.Once upon a time, there was an ancient Roman with really freaking big feet.Something that is not--in no shape or form, absolutely not, no way in hell--a photo

More...

Strange Company - 7/4/2025

Dr. John W. Hughes was a restless, intemperate man whose life never ran smoothly. When his home life turned sour, he found love with a woman half his age. Then, he lost her through an act of deception, and in a fit of drunken rage, Dr. Hughes killed his one true love.Read the full story here: The Bedford Murder.

More...

Murder By Gaslight - 7/5/2025

Soapy Smith STAR NotebookPage 20 - Original copy1884Courtesy of Geri Murphy(Click image to enlarge)

oapy Smith's early empire growth in Denver.Operating the prize package soap sell racket in 1884.

This is page 20, the continuation of page 19, and dated May 6 - May 29, 1884, as well as the continuation of pages 18-19, the beginning of Soapy Smith's criminal empire building in Denver, Colorado.&

More...

Soapy Smith's Soap Box - 6/1/2025

[Editor’s note: Guest writer, Peter Dickson, lives in West Sussex, England and has been working with microfilm copies of The Duncan Campbell Papers from the State Library of NSW, Sydney, Australia. The following are some of his analyses of what he has discovered from reading these papers. Dickson has contributed many transcriptions to the Jamaica […]

More...

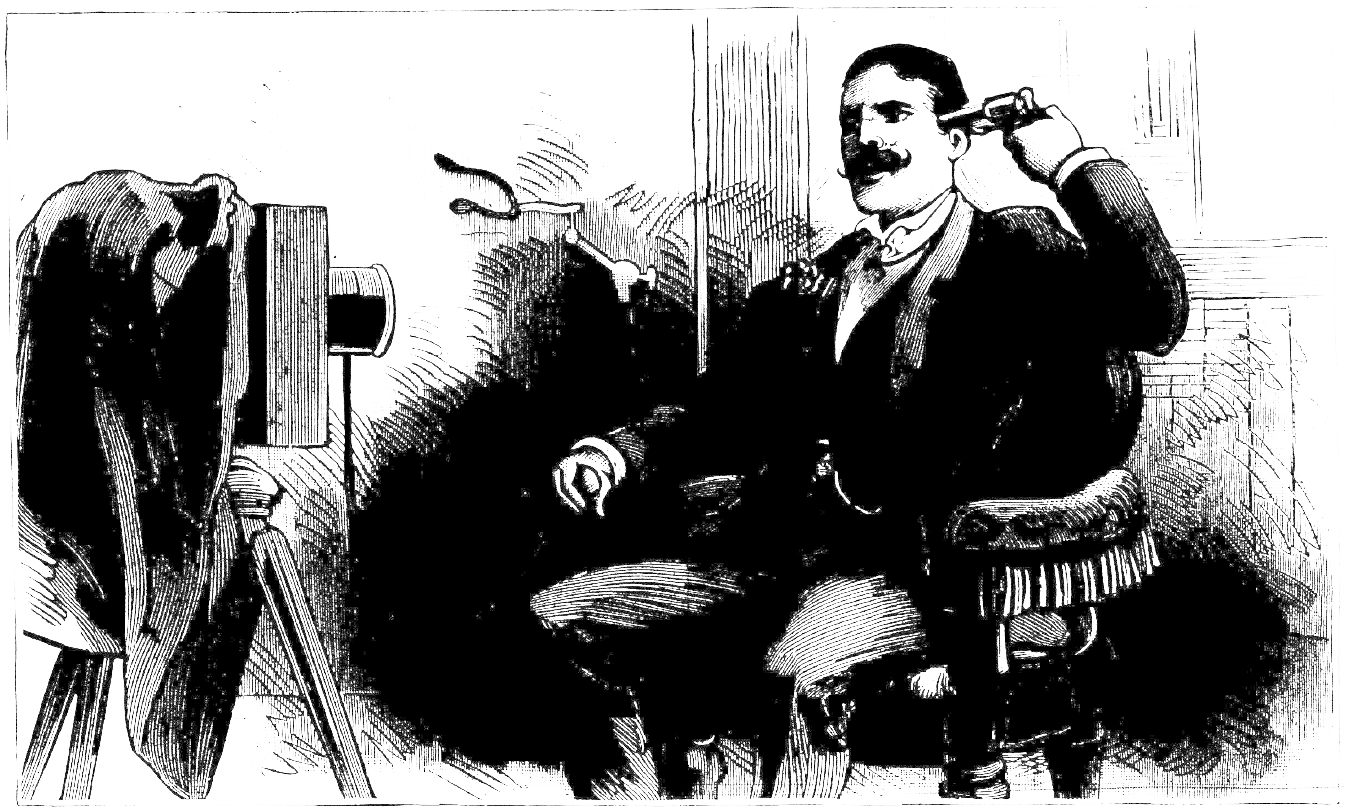

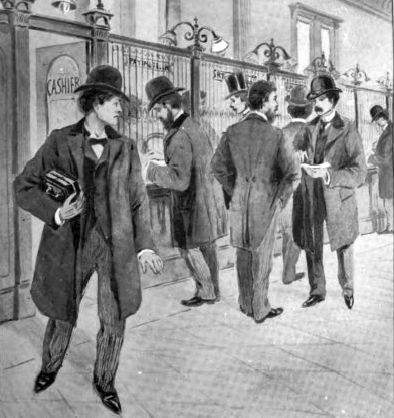

Of the many forms of bank robbery, the bank sneak had the safest, easiest and most lucrative method of all. Holdup men risked their lives and the lives of others by demanding money at the point of a gun. Bank burglars worked in large gangs, with elaborate plans that always involved the physical labor of cutting, pounding, prying or blasting to get though iron bars and steal vaults. But a skilled bank sneak just walked into a bank, took what he wanted and left.

Of the many forms of bank robbery, the bank sneak had the safest, easiest and most lucrative method of all. Holdup men risked their lives and the lives of others by demanding money at the point of a gun. Bank burglars worked in large gangs, with elaborate plans that always involved the physical labor of cutting, pounding, prying or blasting to get though iron bars and steal vaults. But a skilled bank sneak just walked into a bank, took what he wanted and left. Walter Sheridan

Walter Sheridan Horace Hovan

Horace Hovan Chauncey Johnson

Chauncey Johnson