alias: OLD JACK

BURGLAR

Via Newspapers.comFamily banshees can come in different forms, I suppose, but a piano is a new one for me. The “Richmond Independent,” May 1, 1933:The Wetherill family of Continental, O., desire to get rid of their piano, which isn't of the player type. For the third time in less than 12 years, the omen of death has been sounded on the piano. The other night, Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wetherill

More...

Strange Company - 7/9/2025

Wouldn’t you love to have interviewed Lizzie’s physician, Dr. Nomus S. Paige from Taunton, the jail doctor, ? He found her to be of sane mind and we can now confirm that he had Lizzie moved to the Wright’s quarters while she was so ill after her arraignment with bronchitis, tonsilitis and a heavy cold. We learn that she was not returned to her cell as he did not wish a relapse so close to her trial. Dr. Paige was a Dartmouth man, class of 1861. I have yet to produce a photo of him but stay tuned! His house is still standing at 74 Winthrop St, corner of Walnut in Taunton. He was married twice, with 2 children by his second wife Elizabeth Honora “Nora” Colby and they had 2 children,Katherine and Russell who both married and had families. Many of the Paiges are buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Taunton. Dr. Paige died in April of 1919- I bet he had plenty of stories to tell about his famous patient in 1893!! He was a popular Taunton doctor at Morton Hospital and had a distinguished career. Dr. Paige refuted the story that Lizzie was losing her mind being incarcerated at the jail, a story which was appearing in national newspapers just before the trial. Mt. Pleasant Cemetery, Taunton, courtesy of Find A Grave. 74 Winthrop St., corner of Walnut, home of Dr. Paige, courtesy of Google Maps Obituary for Dr. Paige, Boston Globe April 17, 1919

More...

Lizzie Borden: Warps and Wefts - 5/24/2025

The history of New York City’s street corner ice cream vendors goes back at least to the late 19th century, when a man with a pushcart would set himself up and wait for the kids to crowd around. The driver of this wagon in an 1895 photo isn’t exactly the ice cream man. He’s the […]

More...

Ephemeral New York - 7/7/2025

Youth With Executioner by Nuremberg native Albrecht Dürer … although it’s dated to 1493, which was during a period of several years when Dürer worked abroad. November 13 [1617]. Burnt alive here a miller of Manberna, who however was lately … Continue reading

More...

Executed Today - 11/13/2020

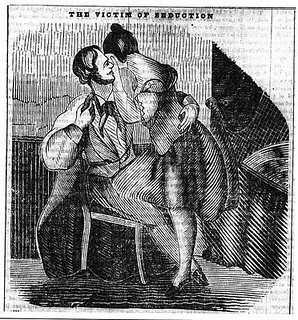

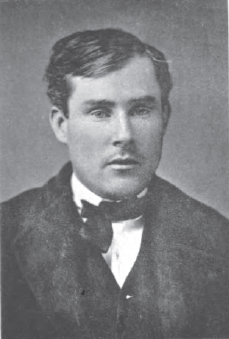

Dr. John W. Hughes was a restless, intemperate man whose life never ran smoothly. When his home life turned sour, he found love with a woman half his age. Then, he lost her through an act of deception, and in a fit of drunken rage, Dr. Hughes killed his one true love.Read the full story here: The Bedford Murder.

More...

Murder By Gaslight - 7/5/2025

Soapy Smith STAR NotebookPage 20 - Original copy1884Courtesy of Geri Murphy(Click image to enlarge)

oapy Smith's early empire growth in Denver.Operating the prize package soap sell racket in 1884.

This is page 20, the continuation of page 19, and dated May 6 - May 29, 1884, as well as the continuation of pages 18-19, the beginning of Soapy Smith's criminal empire building in Denver, Colorado.&

More...

Soapy Smith's Soap Box - 6/1/2025

[Editor’s note: Guest writer, Peter Dickson, lives in West Sussex, England and has been working with microfilm copies of The Duncan Campbell Papers from the State Library of NSW, Sydney, Australia. The following are some of his analyses of what he has discovered from reading these papers. Dickson has contributed many transcriptions to the Jamaica […]

More...