alias: BROWN, CLIFFORD

PICKPOCKET

"The Witches' Cove," Follower of Jan MandijnWelcome to this week's Link Dump!We tip our hat to you!The eldest daughter of Thomas More.That time when tornado ruins became a tourist attraction.In the "Bad Jobs" category, I'd have to put "Removing bodies from Mount Everest" near or at the top of the list.A bizarre family tragedy.A day spent photographing grave monuments.A mysterious Mayan

More...

Strange Company - 7/26/2024

Included in yesterday’s trip to Fall River was a stop at Miss Lizzie’s Coffee shop and a visit to the cellar to see the scene of the tragic demise of the second Mrs. Lawdwick Borden and two of the three little children in 1848. I have been writing about this sad tale since 2010 and had made a previous trip to the cellar some years ago but was unable to get to the spot where the incident occured to get a clear photograph. The tale of Eliza Borden is a very sad, but not uncommon story of post partum depression with a heartrending end. You feel this as you stand in the dark space behind the chimney where Eliza ended her life with a straight razor after dropping 6 month old Holder and his 3 year old sister Eliza Ann into the cellar cistern. Over the years I have found other similar cases, often involving wells and cisterns, and drownings of children followed by suicides of the mothers. These photos show the chimney, cistern pipe, back wall, dirt and brick floor, original floorboards forming the cellar ceiling and what appears to be an original door. To be in the place where this happened is a sobering experience. My thanks to Joe Pereira for allowing us to see and record the place where this sad occurrence unfolded in 1848. R.I.P. Holder, Eliza and Eliza Ann Borden. Visit our Articles section above for more on this story. The coffee shop has won its suit to retain its name and has plans to expand into the shop next door and extend its menu in the near future.

More...

Lizzie Borden: Warps and Wefts - 2/12/2024

The low-rise, mostly commercial stretch of Brooklyn’s 18th Avenue running through Bensonhurst has a historic feel. That’s due in part to the circa-1829 New Utrecht Reformed Church and replica Liberty Pole facing the avenue. But a pocket park a few blocks away at 18th Avenue and 82nd Street contains an even more curious artifact from […]

More...

Ephemeral New York - 7/22/2024

An article I recently wrote for the British online magazine, New Politic, is now available online. The article, “The Criminal Origins of the United States of America,†is about British convict transportation to America, which took place between the years 1718 and 1775, and is the subject of my book, Bound with an Iron Chain: […]

More...

Early American Crime - 12/17/2021

On Saturday, January 25, 1879, George Rowell returned home to Montville, Maine, from a trip to Bath, eighteen miles away. He lived in the house owned by John and Salina McFarland, a married couple in their seventies. Rowell, 40, married their son’s widowed wife, Abby, who had a 14-year-daughter, Cora McFarland. She also had an infant son with Rowell. All six lived together in the Montville

More...

Murder By Gaslight - 7/20/2024

CHIEF OF CONSThe Morning Times(Cripple Creek, Colorado)February 15, 1896Courtesy of Mitch Morrissey

ig Ed Burns robs a dying man?

Mitch Morrissey, a Facebook friend and historian for the Denver District Attorney’s Office, found and published an interesting newspaper piece on "Big Ed" Burns, one of the most notorious characters in the West. Burns was a confidence man and

More...

Soapy Smith's Soap Box - 4/2/2024

Youth With Executioner by Nuremberg native Albrecht Dürer … although it’s dated to 1493, which was during a period of several years when Dürer worked abroad. November 13 [1617]. Burnt alive here a miller of Manberna, who however was lately … Continue reading

More...

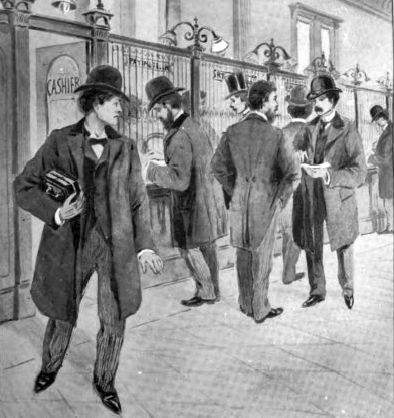

Of the many forms of bank robbery, the bank sneak had the safest, easiest and most lucrative method of all. [more] Holdup men risked their lives and the lives of others by demanding money at the point of a gun. Bank burglars worked in large gangs, with elaborate plans that always involved the physical labor of cutting, pounding, prying or blasting to get though iron bars and steal vaults. But a skilled bank sneak just walked into a bank, took what he wanted and left.

Of the many forms of bank robbery, the bank sneak had the safest, easiest and most lucrative method of all. [more] Holdup men risked their lives and the lives of others by demanding money at the point of a gun. Bank burglars worked in large gangs, with elaborate plans that always involved the physical labor of cutting, pounding, prying or blasting to get though iron bars and steal vaults. But a skilled bank sneak just walked into a bank, took what he wanted and left.