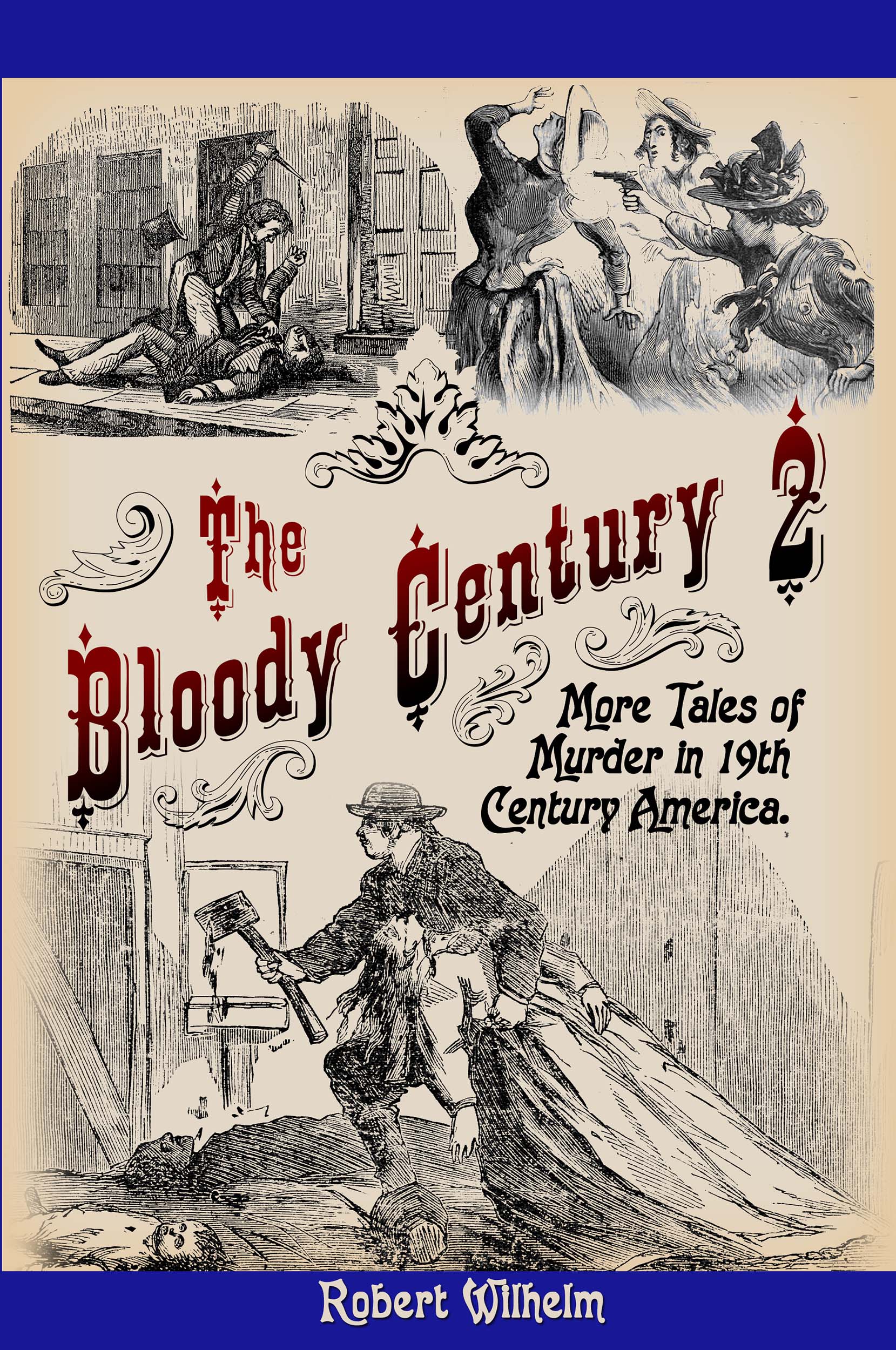

The Last Dip of the Season.

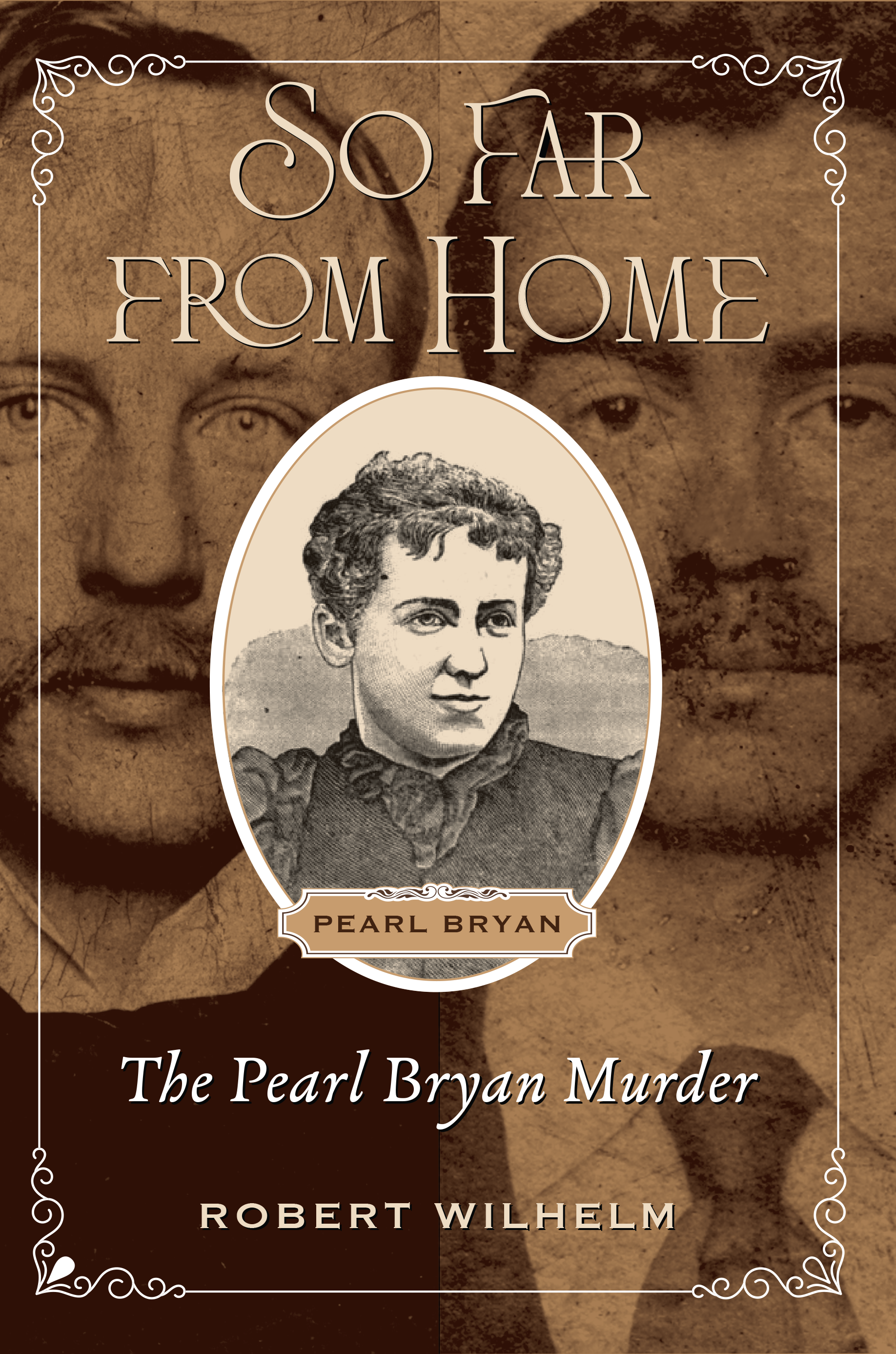

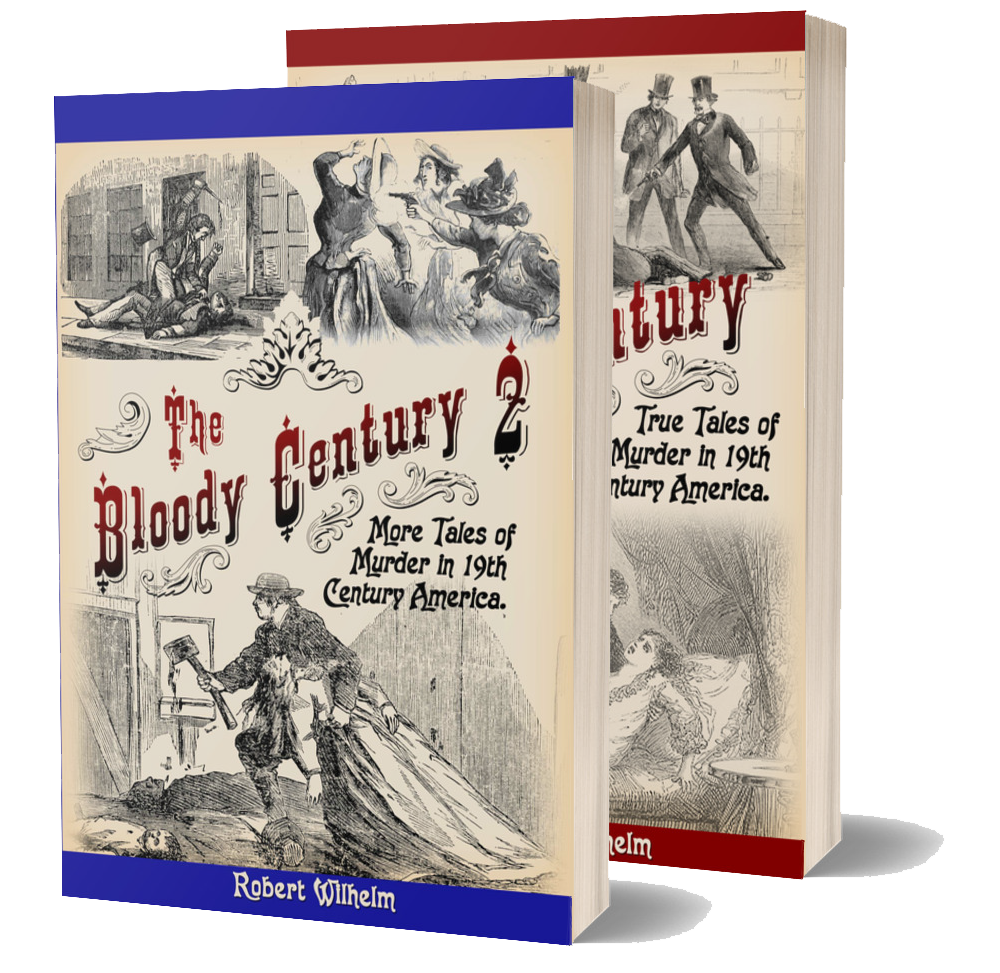

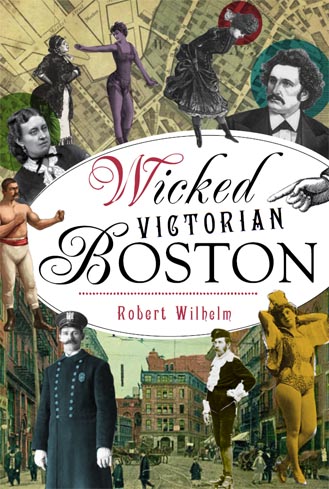

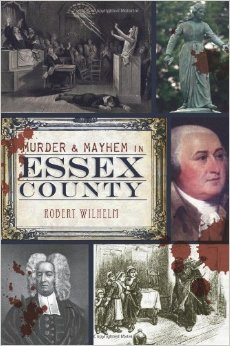

Strange Company - 9/15/2025

Lizzie Borden: Warps and Wefts - 7/26/2025

Ephemeral New York - 9/15/2025

Executed Today - 11/13/2020

Soapy Smith's Soap Box - 8/27/2025

Early American Crime - 2/7/2019

Horatio Alger Story. | The Advent of Spiritualism.

The Last Dip of the Season.

A group of homeless New York Newsboys.

A group of homeless New York Newsboys.The rapid population expansion of New York City in the years following the Civil War was accompanied by an equally rapid expansion of in the population of homeless boys sleeping in alleys and living hand-to-mouth on the city streets. Sometimes taking to the streets to escape abusive fathers, sometimes abandoned by unwed mothers, the waifs had no family connections and no identities beyond the nicknames they gave each other. Though tough and ruggedly independent, to a great extent they survived by taking care of each other.

There were two classes of homeless boys – “street arabs” and “gutter-snipes.” Street arabs were the older, stronger boys. Sturdy and self-reliant, they were always ready to fight for what was theirs, and ready, as well, to fight for the weaker gutter-snipes who looked to them for protection. Gutter-snipes were younger boys—sometimes as young as four or five—brutalized by abusive parents and left to the dangers of the street until they find the protection of an older boy. In time the gutter-snipe would harden into a full-fledged arab with snipes of his own.

The most enterprising of these boys—both street arabs and gutter-snipes—became newsboys hawking the many competitive daily newspapers sold on the streets of the city. Being a newsie required a considerable amount of self-discipline. A newsie had to wake before dawn and arrive at the newspaper with enough money in his pocket to pay for the papers he would be hawking throughout the day. During the regular course of business, they respected each other’s turf and would not interfere with another boys clientele. But a fire, a brawl or any other event that drew a crowd would also draw newsboys competing directly with each other.

A number of societies and agencies were established to aid the homeless boys of New York but the boys were extremely independent and suspicious of handouts. Better to sleep outside than to risk being trapped and taken the House of Refuge. The most successful aid organization was the Newsboy’s Lodging House which offered a bed and bath for six cents a night and a hot supper for four cents. Skeptical at first, the boys came to view the Lodging House as their hotel. Rules were minimal, a gymnasium was available for their use, and reading lessons were provided for those interested.

But even with affordable lodging, many of the boys preferred sleeping outside. They were avid theatre goers and given the choice between a warm bed and a ticket to a play or vaudeville show were likely to choose the latter. Alcohol, gambling and the rest of the urban vices worked to drive the older boys from the straight and narrow. Though the Newsboy’s Lodging House could boast of many triumphs, including homeless boys who went on to graduate from great universities, more often the lessons learned on the street prepared the boys for the fastest growing occupation in the city— crime.

Sources

- Campbell, Helen, Thomas Wallace Knox, and Thomas Byrnes. Darkness and daylight, or, Lights and shadows of New York life: a woman's pictorial record of gospel, temperance, mission, and rescue work "in His Name" .... Hartford, Conn.: A.D. Worthington, 1897.

- Needham, Geo. C.. Street Arabs and gutter snipes The pathetic and humorous side of young vagabond life in the great cities, with records of work for their reclamation.. Boston: D.L. Guernsey, 1884.

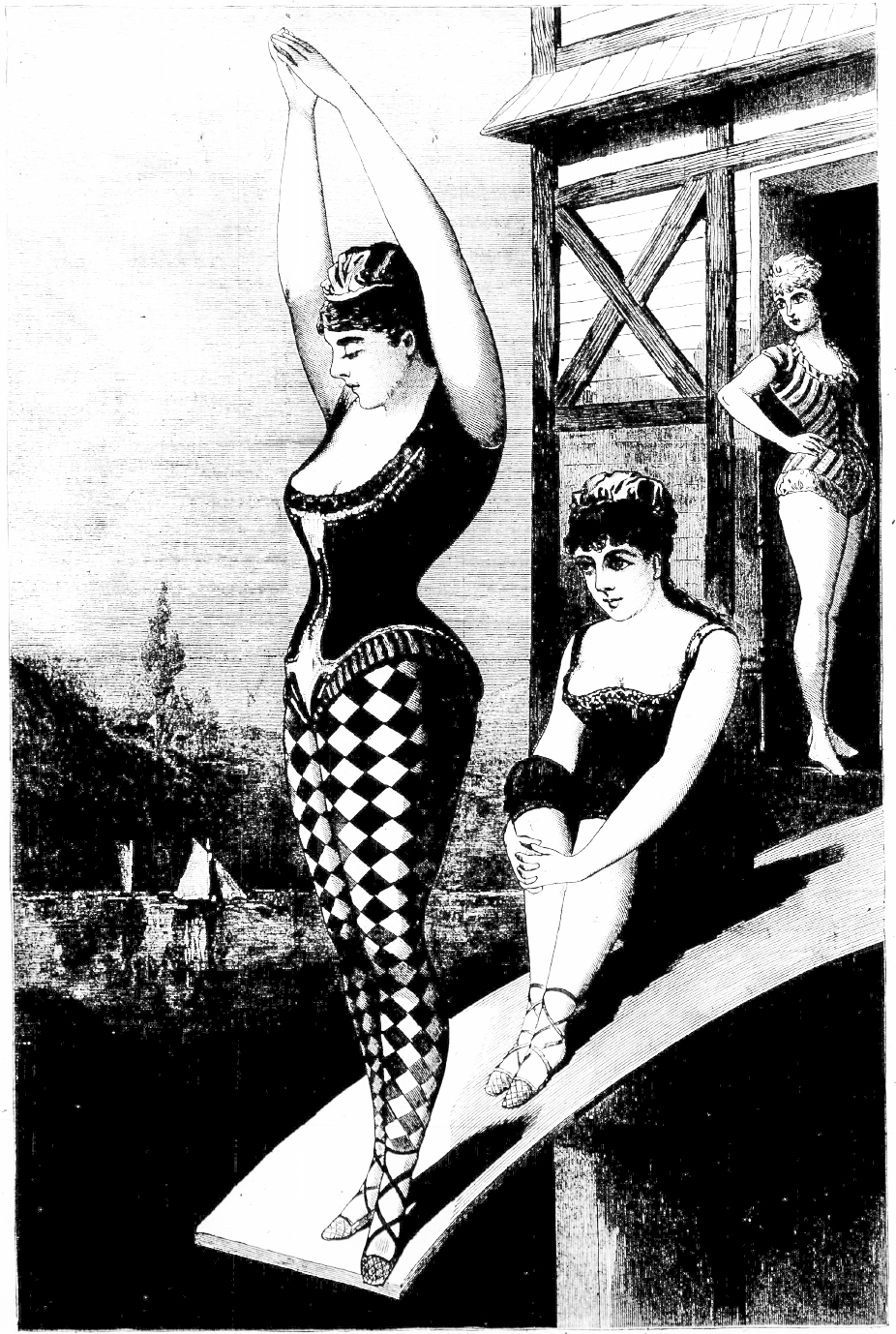

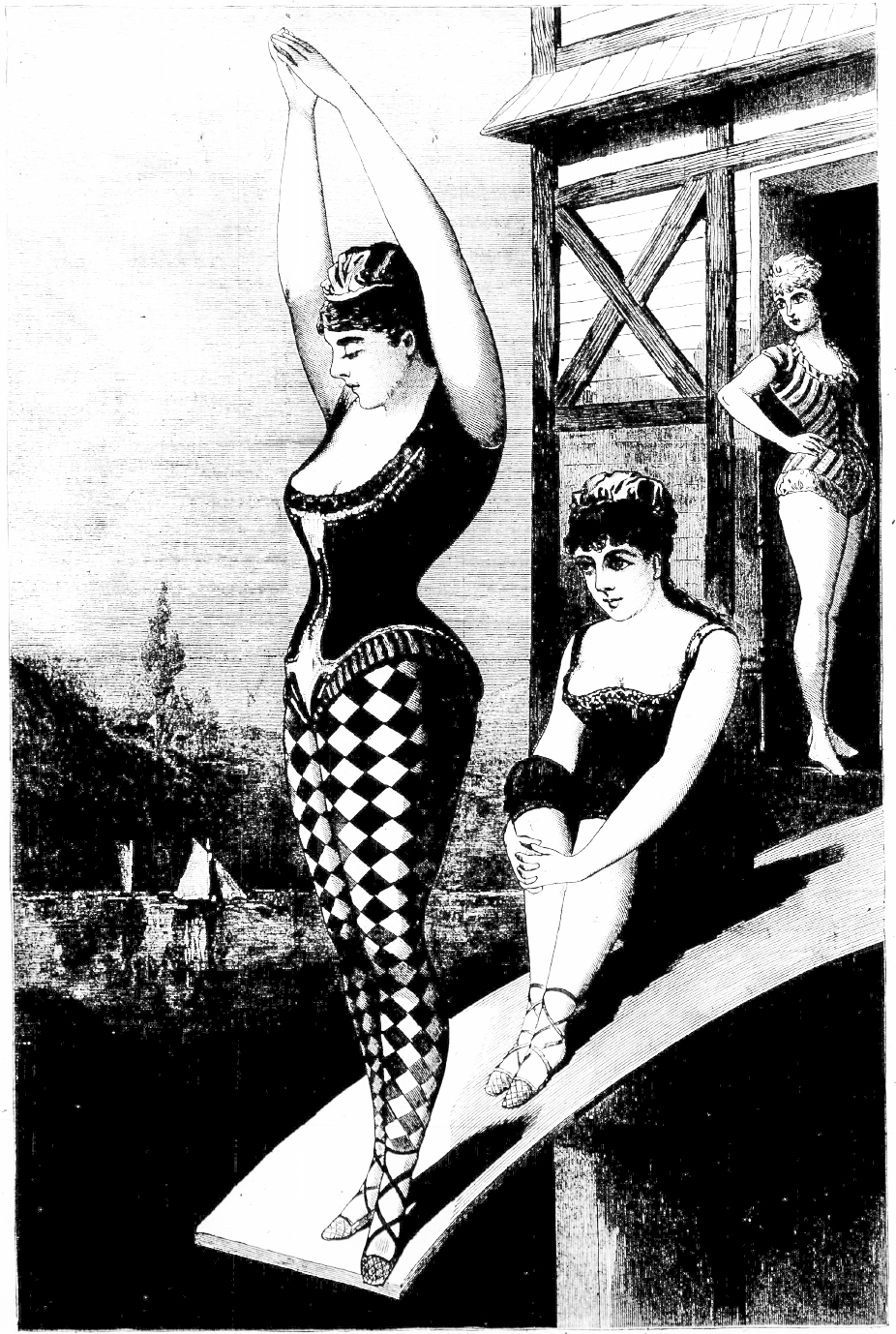

Water witches who frolic with Neptune, no matter how cold his embrace.

Westchester Water Witches

They Won’t Have a Man Around, and Still Enjoy Themselves—Diving as a Fine Art, With a Special View to the Exhibition of Pink Flesh and Pretty Hosiery.

The fair dwellers in some of the charming country sites on the shores of Long Island Sound have invented a means of enjoying themselves, whose novelty will probably recommend it whenever it becomes known before the season is over. In the course of a yachting cruise down the sound last week a Police Gazette artist enjoyed an admirable opportunity to obtain the sketch presented with this number.

The pictures explains itself. A long and elastic spring-board is flown from the gallery of a boathouse, itself built over deep water, so far out as to afford ample profundity for safe diving. The plank itself is some fifteen feet above the surface of the water and straight in advance of its end a light cork buoy is enclosed. The door of the boat house in the rear is open, giving the diver a run of some twenty feet for a start.

The result, seen for the first time, is, to say the least, startling.

An elegant figure clad in a tight-fitting bathing suit of the most improved French model, bounds out of the dark doorway, makes three or four leaps on the swaying plank and is then shot high in the air, a mere flash of striped hosiery and pink flesh, descending a parabola and landing, if she knows how to preserve her balance, with her pointed hands, into the water, clearing the surface like an arrow and vanishing at last in a little circle of boiling foam. The object of the divers is to leap beyond the anchored buoy as far as possible, and a regular record is kept of the distance of the leaps. After rising to the surface the fair swimmers paddle back through the piles on which the boat house is sustained and ascend a comfortable ladder to the club-room, for it is, again.

The boat house is the meeting place of the “Westchester Divers," as they call themselves, who consist of numerous wealthy ladies of the vicinity, with a sprinkling of well-known actresses and professionals in operatic walks.

It is a veritable female paradise, no men being admitted to the hospitalities of the establishment. “We can’t keep you away in your boat, of course,” observed the smiling president to the artist. “But we won’t permit you to land, and you are always glad to get over to the Point where they have excellent lager beer on tap. Are you not thirsty?” The artist considered the hint an excellent one, and took it. He is sorry to say, however that the charming president of the “Westchester Divers” is either no judge or she has never read Sapphire.

Reprinted from The National Police Gazette, October 9, 1880.

Welcome to the National Night Stick

"We follow vice and folly where a police officer dare not show his head, as the small, but intrepid weasel pursues vermin in paths which the licensed cat or dog cannot enter."The Sunday Flash 1841

- 1810s

- 1820s

- 1830s

- 1840s

- 1850s

- 1860s

- 1870s

- 1880

- 1880s

- 1890

- 1890s

- Abduction

- Abortion

- Accident

- Actors

- Adultery

- Advertisement

- African Americans

- Alabama

- Alcohol

- Allan Pinkerton

- America

- Animal

- Assault

- Axe Murder

- Bank Robbery

- Barnum

- Baseball

- Beer

- Bet

- Bicycle

- Billiards

- Bio

- Boston

- Boxing

- Boys

- Broadway

- Brooklyn

- Brothel

- Buffalo

- Burglar

- Burglary

- Burlesque

- California

- Canada

- Cartoon

- Censorship

- Chicago

- children

- Chorus Girls

- Christmas

- Cincinnati

- Civil War

- Clergy

- Clubbing

- College

- Colorado

- Comstock

- Con Game

- Connecticut

- Counterfeit

- Court

- Cowboy

- Crime

- cross-dressing

- Crossdressing

- Cursing

- Dancing

- Deception

- Delinquents

- Denver

- Detectives

- Detroit

- Dime Novels

- Disaster

- Disguise

- Disorderly conduct

- Divorce

- Domestic Violence

- Drowning

- Duel

- Editorial

- Election

- Entertainment

- Event

- Fad

- Family

- Fashion

- Fight

- Fire

- Food

- Football

- Forger

- Fraud

- Gambling

- Gangs

- Georgia

- Great Detectives

- Gunshot

- Hoax

- Holiday

- Horses

- Hotel

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Insanity

- Jail Break

- Jealousy

- Justice

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Little Murders

- Louisiana

- Lynching

- Maine

- Marriage

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Medicine

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Missouri

- Montana

- Murder

- Music

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Orleans

- New Year

- New York

- New York City

- Newsboys

- Newspaper

- Nudity

- Obscenity

- Ohio

- Opium

- Pennsylvania

- Performer

- Petrified man

- Photography

- Pickpocket

- Poisoning

- Police

- Police Gazette

- Politics

- Prank

- Prison

- Prostitution

- Railroad

- Rape

- Rats

- Reform

- Religion

- Reporters

- Revenge

- Rhode Island

- Robbery

- Romance

- Saloon

- San Francisco

- Scandal

- Science

- Seasonal

- Sex

- Slashing

- Society

- Spiritualism

- Sport

- Sports

- Spousal Abuse

- St. Louis

- Stabbing

- Steamboat

- Steamship

- Suicide

- Summer

- Tammany Hall

- Temperance

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Theatre

- Theft

- Thomas Byrnes

- Valentine

- Vigilantes

- Voyeur

- War

- Washington D.C.

- Wife beaters

- Winter

- Women